The media and general public will be hailing Ofcom’s spectrum auction as a huge success. It raised over £1.355 billion for the Treasury. This has now become the popular measure for the success of a spectrum auction. In 2003 spectrum in the 3.4 GHz band only fetched £175,000 per MHz, which would be £262,000 at today’s prices adjusted for inflation. At the 5G spectrum auction it fetched £7.83m per MHz. If Ofcom was no more than a branch of the Inland Revenue it was a very good outcome.

However, as Ofcom constantly reminds us, the purpose of a spectrum auction is not to raise money for the Treasure but to get the spectrum into the hands of those that will make the best use of it. Against this measure, how successful was the 5G spectrum auction?

The 5G auction outcome can mark-up two positives:

However, there are some down-sides when it comes to the release of the 3.4 GHz spectrum:

Let’s take each in turn:

The reserve for price for each 5 MHz lot of 3.4 GHz spectrum was £1m and there were thirty lots. If the spectrum had sold for the reserve price, the industry collectively would have paid £30m. Instead they paid £1.16 billion. What was going on?

Branding it “a 5G pioneer band” probably sprinkled a bit of star-dust on the spectrum but that was also true of the Irish 5G auction. Vodafone UK paid £7.56m per MHz for its 3.4 GHz spectrum whereas my calculations show that Vodafone Ireland paid £1.53 per MHz on a comparable basis. That is nearly one-fifth of the price. (Note: my calculation averaged the city and rural spectrum prices and adjusted for the two different population sizes). We also see later that the new entrant had no effect on the price.

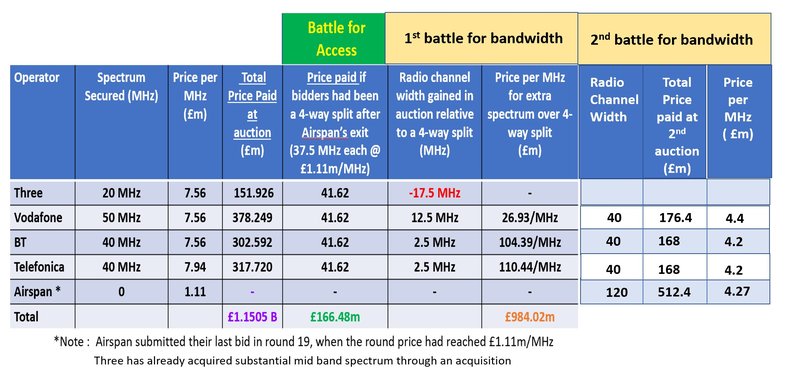

This only leaves the Ofcom auction design generating over-heating. Let’s look at some numbers:

If the four mobile operators had entered the auction to just to secure equal shares ie 37.5 MHz each, they would have only paid £0.2m per MHz instead of around £7.5m ie the price at the point when Airspan left the acution. This price inflation came from the market approach to auction design that allowed one mobile operator to seek more than “equal shares” in a zero sum game. What is particular in this auction design is that one operator seeking a substantial increase sent the price for the others rocketing just for them to almost standstill relative to the “fair share value”:

Ofcom rejected the idea of auctioning large blocks of spectrum in favour of auctioning small increments of bandwidth to test the market appetitie for bandwidth and the result was to make “incremental bandwidth” almost penal for those trying just to stay in the 5G market. The penalty for a single new entrant party behaving entirely rationally was to have to leave the auction with no spectrum whatsoever. This is what happened to Airspan.

The outcome of the auction is to leave H3G with 60 MHz, Vodafone with 50 MHz, BT with 40 MHz and O2 with 40 MHz. Common sense would suggest that the mobile operator with the largest customer base could afford to secure the most spectrum and the mobile operator with the smallest customer base would finish with the least spectrum. The market shares in 2018 are in the ranking order: BT, O2, Vodafone and H3G. In other words the outcome of this auction is the complete inverse of a rational economic outcome.

A credible new entrant, Airspan, came financed to acquire spectrum based on what they had paid for spectrum in other countries. They were knocked out of the 3.4 GHz auction after only a few rounds. This is a blow to competition and also a blow to consumers, as Airspan’s business plan was to be a neutral host, a model that thrives in parts of the country where competition fails to deliver early coverage.

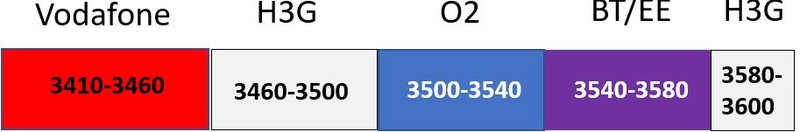

The auction was in two stages. The first settles how much spectrum each bidder gets and the second determines exactly where in the band their spectrum will be assigned. This was made more complicated by an incumbent service, called UK broadband, that Ofcom allowed to stay in place. Subsequently, the company was bought by H3G, so even before auction began H3G had 40 MHz of spectrum in the band. The following band plan emerged from the auction assignment stage:

The decision of H3G to leave UK Broadband 40 MHz of spectrum where it was has resulted in their 60 MHz being fragmented. But it also left no choice where Vodafone, O2 and BT/EE could put their assignments as only lower part had 50 MHz space to accommodate Vodafone’s 50 MHz of spectrum. However, it is not the only fragmentation issue – the spectrum of the two site sharing groups has been split up. The band plan is a mess. Worse than that expensive filters are now needed by the bidders to protect the incumbant services.

The first three generations of cellular mobile released spectrum on an exclusive national basis but this was under pinned by a national coverage obligation. The 2.6 GHz spectrum (4G) auction was the first time cellular mobile spectrum was released on a national basis with no coverage obligation. Five years after the 4G auction the 2.6 GHz spectrum is only fully deployed over 2% of the UK. In other words over 98% of the country valuable 4G spectrum is wasting away every single day. Now my expectation is for 3.6 GHz 5G networks to be rolled out much further than 4G networks at 2.6 GHz have been since there are more mobile operators with 5G spectrum. However, coverage that is driven solely by capacity peaks is unlikely to extend much beyond 20% of the UK. To have prime 5G spectrum being wasted across 80% of the UK would be a shocking statistic for a regulatory authoritiy charged with making efficient use of the spectrum and bad news for all the rural citizens that could have had coverage benefits from 5G small cells connected to the ends of the growing reach of fibre optic cables being promoted by the Government and Ofcom.

The second 5G mid band spectrum auction saw more rational bidding as shown in figure 1. The net outcome of the market mechanism approach to spectrum efficiency is shown:

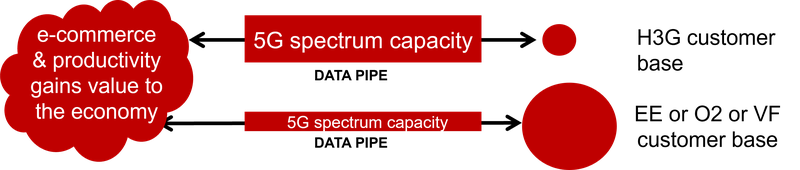

The optimal use of the spectrum is where the maximum amount of mobile data (which carries the economic value to the country) has been transported. Having the largest data pipe matched to the largest cohort of users and the smallest data pipe matched to the smallest cohort of customers will maximie the amount of data that can be transported. The Ofcom spectrum auctions (and trading) has delived the exact opposite.

Conclusion

The sale of the 2.3 GHz spectrum to O2 is a reasonably successful outcome for the country. However, the outcome of the sale of the 5G pioneer band spectrum at 3.4-3.8 GHz, illustrated in figure 2 has shown the market mechanisms approach to spectrum allocation has not delivered optimal spectrum efficiency.

Read more

The pressing need across Europe is for pro-investment mobile regulation. This book describes, for the first time, what a pro-investment mobile regulatory framework might look like.

Casting the Nets provides an unparalleled insight into the great digital transformation of Britain’s communications networks over the period 1984-2004. It gives a graphic description of industrial policy-in-action and brings to life what is involved.

All content here (c) copyright of Stephen Temple